Transport

How Threapwood almost became a railway junction

Railway transport in Britain developed rapidly in the 1840s with many small companies providing links between most major towns. The network continued to grow after that with the railway companies seeking new routes, either to compete with existing providers, or to extend their customer base. At the same time, the process of amalgamation of railway companies also began, with existing routes coming under common ownership and coordinated planning of timetables.

The Wrexham Mold and Connah's Quay Railway Company(WMCQR) had been established in 1862 to provide a rail link from Wrexham to Buckley, from where the Buckley Railway company already had begun a line to Connah's Quay to connect with the London and North Western Railway(LNWR) line from Holyhead to Chester. This provided an outlet for the mines and industries of north east Wales both to the LNWR and also to the Great Western Railway(GWR) which already had a station in Wrexham.

|

Plans drawn up in 1865 |

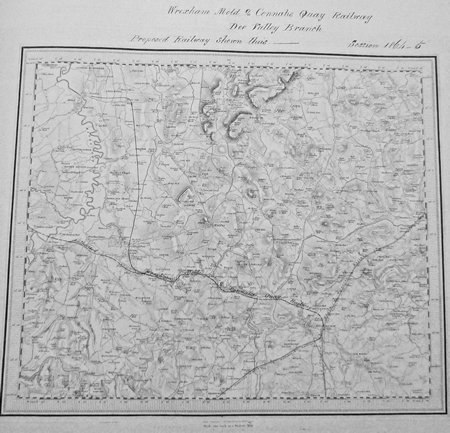

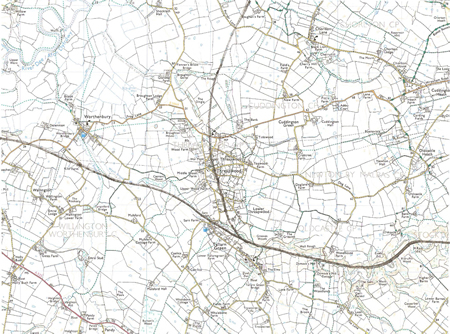

In 1862 the WMCQR sought approval for a line to connect Wrexham to Whitchurch (from where there was already a line to the developing railway hub at Crewe). The route of this line followed the Wych Brook from Worthenbury, south of Threapwood and across to Grindley Brook. Two years later the company applied to parliament for approval for a further extension from the route of this line to Farndon. The company's plans show that the route would have left the Wrexham/Whitchurch line near Greaves Wood and swung through Threapwood before heading north to Farndon. The Company's engineers (Mr R Piercy and Mr B Piercy) drew up detailed plans (in Chester Records Office) showing who were the owners, tenants and occupiers of each field the route would cross. Despite the efforts made to plan these routes and to secure Parliamentary approval (given on 25 July 1864 and 29 June 1865 respectively), neither extension to the railway was ever constructed. Had they been built, it is likely that a station would have been established in Threapwood to allow for passengers and freight changing from one line to the other.

|

Plans of line dated 1864-5 |

|

Line depicted on modern map |

During research of these proposals, one other interesting item came to light regarding the WMCQR. In a debate in the House of Lords on 5 June 1882 the Duke of Westminster explained that his mining company had been frustrated by the GWR who would not provide economic means of delivering coal to Connah's Quay. The WMCQR were seeking permission to build further lines in north east Wales so as to remove the need to use any GWR track in getting to the dock facilities. A railway map of the area was described by the Earl of Dartmouth as 'resembling an octopus', with much duplication of routes because of the conflicting economic interests of railway companies and their respective owners. However, of 498 landowners affected by the WMCQR proposal, only one objected - the GWR!! The debate in the Lords concerned whether the select committee reviewing the bill was sufficiently impartial. This would seem difficult to prove. On the one hand the Duke of Westminster was a major landowner with interests in many of the collieries seeking a route to the docks, but on the other hand Lord Aberdare (from the Select Committee) was a director of GWR. Their Lordships eventually agreed that a new committee should reconsider the proposals and in the following year, approval for the line was granted.

Canal mania and Threapwood

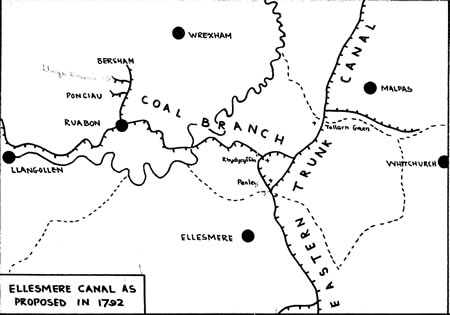

Following the Duke of Bridgewater's success in 1761 in constructing a canal to speed delivery of coal from his mines at Worsley to Manchester, the British canal network grew rapidly. By the 1790's 'canal mania' had gripped the country. Many proposals were fanciful and a lot of canal companies never made any money for their investors. However the Ellesmere Canal company, which developed a network of canals radiating from Ellesmere, was successful for a number of years. The company aimed to link the rivers Severn and Mersey and to profit from the transportation of coal, stone and agricultural products which were difficult to move over land.

Initial work focussed on the route across the Wirral from Chester to what became Ellesmere Port and on the mining/quarrying area around Ruabon. In both cases, short sections of canal had immediate commercial value while the plans for the grander scheme of a network of canals between the Severn and the Dee Valley were developed.

|

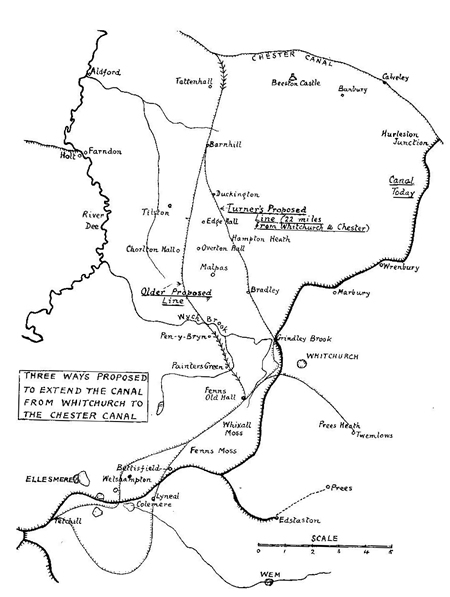

This map shows a proposal from 1792 for one branch of the canal network to pass through the Wych Valley towards Whitchurch. |

In order to understand this proposal it is necessary to look at a wider map of the Ellesmere Canal network and to remember the ultimate objective of linking the Severn and the Mersey. With the link from Chester to Ellesmere Port in place, the goal was to complete a link from Shrewsbury to Chester. A number of competing routes were suggested, of which the above was one of a number of Eastern routes which were favoured over the original plan for the canal to follow the western side of the Dee Valley from Ruabon to Wrexham, Pulford and Chester. The Eastern routes made use of the Nantwich to Chester canal which was completed in 1779. The Ellesmere Canal company built a canal from Ruabon to Welshfrankton (passing over aquaducts at Chirk and Pontcysylte completed in 1805) and by the same date the line from Welshfrankton via Grindley Brook to Hurleston (on the Chester Canal) was complete.

The alternative route would have had an incline to reach the Chester Canal at Tattenhall and therefore water would have flowed back towards Ellesmere. This would have been a serious loss of water from the Chester Canal, a consequence unlikely to be acceptable to the already established canal company. The strength of their negotiating position may well have determined the route of the linking canal and thus ensured that Threapwood was not directly affected by the boom in canal construction.